| The Wooden Press is Replaced by Iron Hand Presses | |||

See this page larger here. |

|

|

|

| Joseph Moxon

Much information about type founding was preserved by Joseph Moxon who published a series of works on the mechanical arts (blacksmithing, carpentry, etc) in his Mechanick Exercises, Vol. 2, 1683. Included therein was Mechanick Exercises in the Whole Art of Printing describing the complete process of letter design, punch cutting, foundry processes and printing.

|

Letterpress

The process of surface printing, (ink on metal surface to paper) was the primary means for printing books for most of printing history. In the 21st century only fine book presses using metal type (or polymer plates on a type-high carrier). In the letterpress era the properly equipped print shop would own large quantities of type sorted into drawers or type cases. Two sets of cases were used for each font—one for capitals, italic or small caps, fractions and lesser used characters and the other for figures, points, spaces, ligatures and lower case characters. During type setting the caps case was positioned above the lowercase—the configuration supplied the names upper case and lower case. There were many type case configurations, some combined both the upper and lower into one double case. Today the most common typecase used in fine press bookshops is the California case. See a full description of it on Briar Press site. The final steps of placing the type onto the press type bed and locking up the form in position is called make ready. |

The

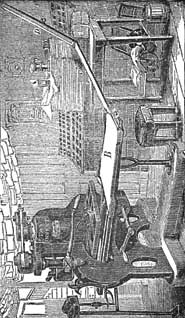

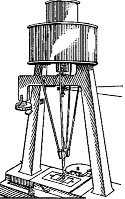

Stanhope Press

Gutenberg and his descendants used wooden presses but in 1800, CHARLES MAHON, (Earl Stanhope) (1753–1816) introduced the first hand press with an iron frame. Capable of printing 480 pages per hour it was stronger and allowed for a larger impression. Through a combination of levers Stanhope's model used 90% less force and held up longer than a wooden press. You can read about the Stanhope press in more detail at British letterpress. We just had to put this picture of the Stanhope in as it appeared on page 364 of Practical printing: A handbook of the art of typography by John Southward. In 1884 Southward sums up the printing world of his day, "There are several varieties of presses in use at the present day. There is the old wooden press, still to be found in some small offices in London and the country. There are also the iron Stanhope press, the Britannia, the Imperial, and one or two others; but in the best offices there are hardly used nor worth pulling proofs upon. Practically there are only two presses in actual use, the Columbian and the Albion." |

|

| Cylinder and Steam Powered Presses | |||

|

|

||

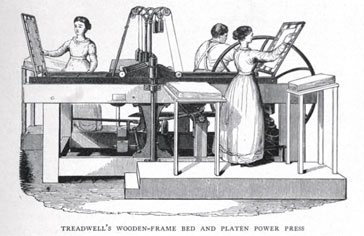

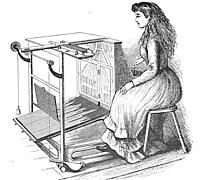

Women in the Pressroom Just because graphic design survey books haven't bothered to report on women in the press room (or for that matter in graphic design prior to the late 1800's) doesn't mean they weren't there. Despite the party line that that printing was strictly a "man's occupation" there is much evidence to the contrary. Women printers were, however, mostly given the tedious and mind-numbing tasks or those that held no promise for advancement. In the press shop that meant feeding sheets onto and taking them off of the press. In the type foundry women were either "rubbers" who completed the final finish on type or packagers of type. Many women set type. In the 18th century there were training schools devoted to teaching women to type set. It was only when the printer's unions were formed that women were boxed out of type and printing. While it looks tame and safe in the illustration (above), there were presses in which hands and fingers could be pinched or lost, and presses at which a woman had to stand for back breaking hours on end to feed the paper into the press.

|

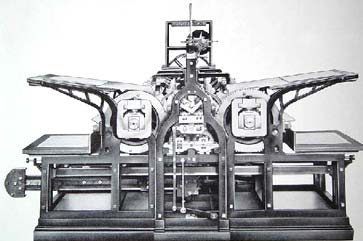

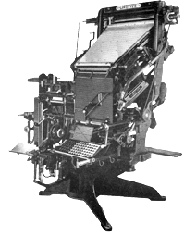

Cylinders & Steam Power Two ideas altered the design of the printing press radically: use of steam power for running the machinery, and second the replacement of the printing flatbed with the rotary motion of cylinders. German printer Friedrich Koenig (1774–1833) worked on a series of steam operated presses in England. His 1814 model (above right) was purchased by The Times of London, assuring commercial success for Koenig's backers. The printers at newspaper were not so enthusiastic, realizing that the new machine would put many of them out of work. Violence was averted when management promised to find employment for any displaced employees. Koenig, who faced legal and financial obstacles in England, returned to Germany where he designed the first "perfecting" press—one that printed both sides of the sheet in one pass. 3

|

Bullock's Perfecting Web Press 4 |

|

| Rotary bed presses

The steam powered rotary printing press, invented in 1843 in the United States by Richard M. Hoe, allowed millions of copies of a page in a single day. Mass production of printed works flourished after the transition to rolled paper as continuous feed allowed the presses to run at a much faster pace. 3 |

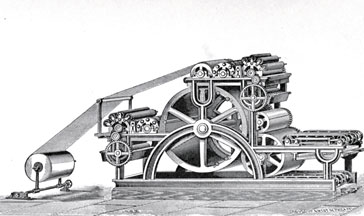

The Perfecting Web Press 1865

Philadelphia's William Bullock developed the first press that allowed for continuous large rolls of paper to be automatically fed through the rollers and to be printed simultaneously on both sides—eliminating the laborious task of hand feeding. The press also folded the paper and featured a sharp serrated knife to automatically cut the printed sheets. The press could print up to 12,000 sheets an hour; later improvements raised the speed to up to 30,000 sheets an hour. 4 |

||

| Advances in Type Casting : Letters, Syllables and Entire Lines | |||

|

|

|

|

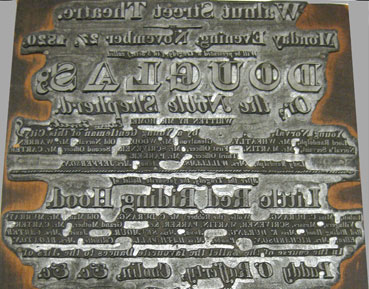

Stereotype, 1725

Above images courtesy of Philadelphia Free Library Theatre Collection and Rare Book Department. |

The Stereotype Process

|

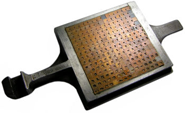

Casting Partial Words

Monotype/ Casting Letters input from a keyboard. In 1887 Tolbert Lanston (1844-1914) patented the Monotype typesetter, which produced individual characters. Individual letters were cast 'on the fly' in order as dictated by a pre-punched ribbon. This eliminating the need to pick cold type by hand. The product of a monotype caster was more durable than linotype and, because the letters were individual, could be reused. See a monotype keypunch machine. The object above is a monotype matrix for casting the individual characters of a complete font. |

Casting a Line of Type The Linotype produces a solid "line of type." It was used for generations by newspapers and general printers. A one-person machine: the operator sits in front with the copy to be set near the keyboard. The machine is adjusted for the required point size and line length and the type metal heated to about 550 F.

Pressed keys trigger a mechanism that releases the matrices—brass pieces in which the characters or dies are stamped. (above) The matrices travel from the magazine channels on a miniature conveyor belt, into the assembler box—the composing stick of the Linotype. The final result was one full line of type. Unable to be reused, the type was returned to molten metal for new casting.6 |

| Mechanization of Punchcutting | |||

|

|

|

|

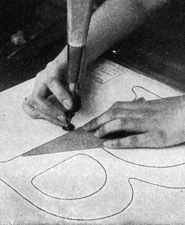

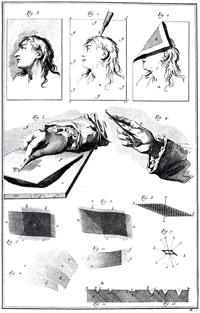

The End of Punchcutting 1884 American typeface designer Linn Boyd Benton created the Benton Pantograph, an engraving machine capable not only of scaling font design patterns to a variety of sizes, but also condensing, extending and slanting the design. The introduction of this machine meant that one could create a punch without the extensive training that traditional punchcutting required. Out with the punchcutter also meant out with the critical eye of the artist letter cutter. |

The process begins with a tracing of a letter design which is translated into a brass master. All surplus brass is routed away from the relief matrice. (above) The brass matrice is placed into the pantograph machine and traced with one arm of the device while a cutting tool on another arm engraves the letter at the required size.

|

In an interview by Mark Solsburg, Mathew Carter spoke of the repercussions of the pantograph. “A Milwaukee engineer named Linn Boyd Benton put the first 'nail in the coffin' of local foundries in 1884 when he invented a pantographic punchcutter, a router-like engraving machine for cutting the steel punches for type. That was the most important technical development in typography since Gutenberg's invention of variable-width type molds in the 15th century.” |

Mathematically, the pantograph works in affine transformation which is the fundamental geometric operation of most systems of digital typography today, including PostScript. Above, a woman typecaster demonstrates a foot operated keyboard apparatus. Suggested Reading for graphic design insomniacs, History of Composing Machines, John Thompson, 1904. |

| Click here to skip to Cold Type (Phototype) | |||

| New Technology for Introducing Tone and Delicacy into Illustrations | |||

|

|

10 |

|

Wood Engraving The art of wood carving was advanced into wood engraving near the end of the 18th century. Englishman Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) a printmaker-poet, popularized a technique in which extremely hard boxwood was cut across the grain, allowing for more fine detail than the normal practice of cutting along the grain. In addition to the fine detail these wooden blocks lasted longer than copper plates because relief printing uses less pressure than copper plate requires high pressure. Bewick also created a new style he termed "white-line engraving.," Previously wood was cut away to reveal black lines, however Bewick would gouge out white lines from a black field. Above Top |

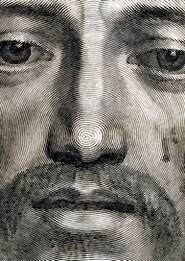

Intaglio Intaglio, an Italian word for engraving, describes any printmaking process by which ink is transferred to paper from below the surface. Ink is forced into engraved lines, or tones, and then the surface of the plate is wiped clean. The press is constructed to deliver a rolling pressure to drive the paper into the lines to lift out the ink. A drawback of intaglio is that it is could not be printed on the same press as metal type. This artistic process preceded the more commercially viable 19th century rotogravure, a method that allow ed the use of a very fine screened image. The method of image photo transfer onto carbon tissue covered with light-sensitive gelatin was discovered, and was the beginning of rotogravure In gravure printing, the image is engraved onto a cylinder for use on a rotary printing press. Once a staple of newspaper photo features, the rotogravure process is still used for commercial printing of magazines, postcards, and corrugated (cardboard) product packaging. 9 |

Types of Engraving Engraving Etching Aquatint

|

Copper Plate Engraving Copperplate script was prevalent in the 19th century, but was used as early as in the 16th century in Europe. As a result, the term "copperplate" is mostly used to refer to any old-fashioned, tidy handwriting. This style of calligraphy is different from that produced by angled nibs in that the thickness of the stroke is determined by the pressure applied when writing, instead of nib angle in relation to the writing surface. All copperplate forms (minuscule, majuscules, numbers, and punctuation) are written at a letter slant of 55 degrees from the horizontal. Copper plate engraving allowed 17th century writing masters, including Jan van de Velde, Maria Strick and Ester Inglis to publish their instructional calligraphy books. Their creative style and innovative letter design influenced commercial metal letter design. The name copperplate is attached to a number of digital fonts.

|

| Advances in Paper Making | |||

|

click here for larger version |

|

|

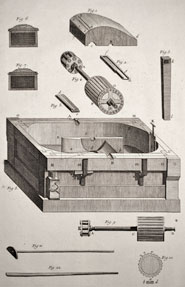

Hollander Beater, 1680 The Hollander beater, a Dutch invention from the mid-seventeenth century, was designed to use windmill power to replace the heavy water wheel powered stampers that had been the standard in the papermaking trade. |

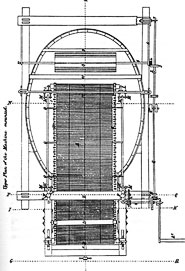

Continuous Paper Rolls Nicholas Louis Robert (1761-1828) invented a process to produce continuous rolls of paper. Robert, previously a artilleryman in the French army, worked for a time as a proof reader in the French printing house of Pierre Francois Didot. He moved to the paper mill of Leger Didot and there he was allowed to experiment with his attempts at making continuous rolls of paper. The image above is an overhead view of a drawing for Robert's 1801 patent application. (Click here to see if larger) Essentially a conveyer belt of wire carried the paper pulp from the vat to a take up roll. "...without machine-made paper the prodigious 19th century growth of cheap printed materials and the resultant dissemination of knowledge an information would not have taken place. The availably of paper in endless rolls made possible the invention of high-speed rotary printing which today accounts for the bulks of all printer products the most commonest being books, newspapers magazines and packaging materials." 13

|

Paper from Wood For centuries paper was made from rags and cotton but as the demand for paper grew it outstripped the raw material reserves. Charles Fenerty (1821-1892) of Halifax made the first paper from wood pulp (newsprint) in 1838. Part of his process was based upon his observations of wasps who built nests He neglected to patent his invention and others did patent papermaking processes based on wood fiber. A German weaver Friedrich Gottlob Keller (1816-1895) , also invented a groundwood process of papermaking in the 1840s. He did copyright his process. The introduction of wood pulp paper to books meant cheaper but less durable products. The process of pulping wood included the use of harsh chemical acids which caused the paper to discolor and become brittle and breakable in a rather short time. |

|

| Footnotes | |||

1 2 3 4 |

5 7 8 |

9 10 11 |

12 13 |

| Copyrights | |||

| ©Designhistory.org 2011 | For Permission Info click here | ||